Intro to Redux

This segment covers👇 You can read the text in 11 minutes. Solving the exercises might take longer.

Welcome to the Redux part of this workshop. Today we're going to build a small StubHub app that:

- loads events in San Francisco from StubHub's API

- lets you find what you want

- add it to a shopping car

- fake buy it

To build it we're going use a few different opensource packages. Redux will help us manage state, Downshift will help us build filtering, redux-form will help us manage the checkout form, and we'll use styled components for styling.

But let's start at the beginning. What is Redux? What's the point?

Why Redux

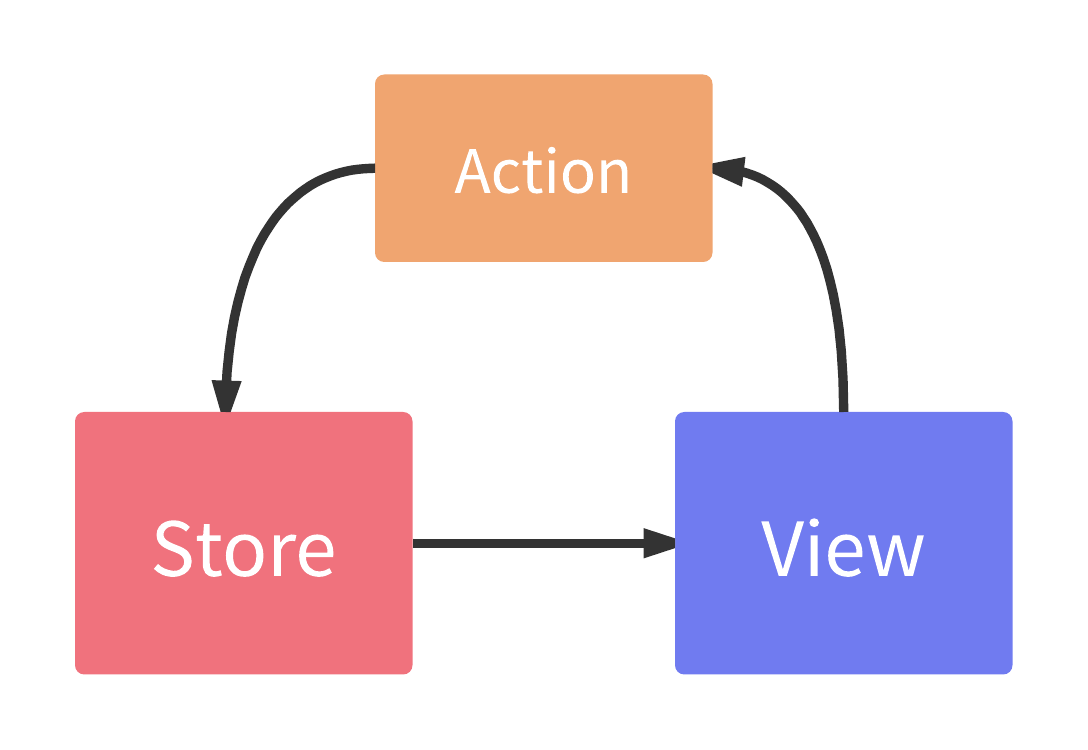

Redux is a state management system built on the unidirectional dataflow principle. Data lives in a central repository of truth and flows down into your components via props. Those components issue actions to change state.

In our earlier examples we achieved this effect by using the top component as a sort of store. Info about our entire app state went into a top component this.state. Data flowed down via props and we used callbacks to move information back up and change state.

This works great for small apps and one-off projects, but as your app and your team grows, it gets messy.

Say you have a button that lives in a component that's nested 10 levels deep. All those 10 levels have to know about the stuff your button needs, they have to pass down props, they have to pass callbacks.

Kind of annoying ...

Then your designer says "You know what, we should move that button". Great, you say and roll up your sleeves to change the entire hierarchy leading to that button. Every little component that was passing props and callback that button was using needs to change.

And then you get to rewire it into a new spot in its hierarchy. Wonderful.

<swizec demonstrates on a whiteboard>

Remind Swizec to take a photo and put it here for posterity.

How Redux solves the refactoring problem

Redux solves this problem in a couple of ways.

- The data store becomes globally accessible. Any component that needs access can get it directly from anywhere in the app. No more long prop-passing chains.

- Anyone can fire an action from anywhere. No more long callback-passing chains.

- The shape of your business logic becomes detangled from the shape of your UI design.

That last part has been most helpful in my own projects.

When you can look at your app's whole business logic in an abstract way that's separate from your UI, and your UI is just an expression of app state ... well ... life is easier :D

You can think about, develop, and test your logic and your UI separately. Components render, Redux machinery deals with state.

Your whole app becomes a state machine, in fact.

UI as a state machine

With good separation of concerns between your business logic and your rendering logic, you can start to think of your app as a state machine. This has several benefits:

- Easier debugging – if you know all of the state in one moment, you can replicate it as many times as you want

- Time-traveling – record state transitions, replay them

- Always know what action caused a change to happen

- Easy to tell exactly how an action affects state

With small apps, you can draw out the entire state machine and keep it in your mind's eye as you work. You'd be surprised for how big of an app this still works.

As your app grows it becomes more like a combination of smaller state machines. While this makes it harder to understand your app as a whole, idiomatic use of Redux still ensures that different state machines don't bleed into one another. This means understanding them separately is okay and works well.

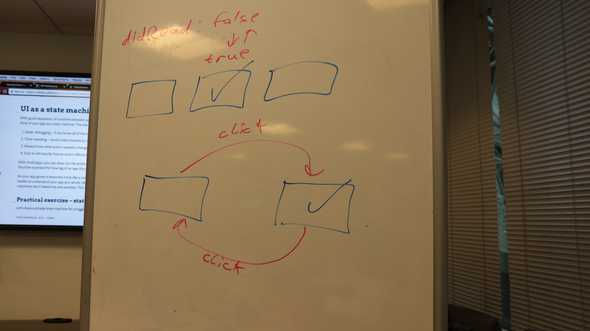

Practical exercise – state machine for a toggle

Let's draw a simple state machine for a toggle. Just to get our feet wet.

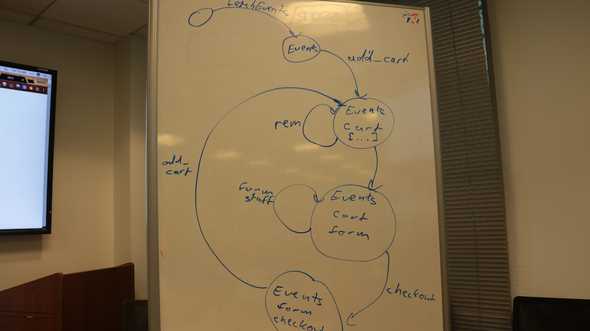

Practical exercise – state machine for our app

Something more complex. Let's draw a state machine for our StubHub app together.

Keep this in mind as we build our app in the next section. It will help you decide what code to write.

Smart and Dumb components

A common pattern when separating your business and view logic is to have smart and dumb components.

Smart components are those that are aware of your data store. They read values from Redux, issue actions, and are generally aware that Redux exists.

Dumb components are those that render purely from props and issue callbacks, which they get from props, to make changes. These have no idea that Redux exists.

Redux vs MobX

As you research state management libraries for React apps, you are likely to come upon two main competitors: Redux and MobX.

Redux follows a functional programming approach. Every change creates a new copy of your state. This is super safe but smells wasteful as your app grows (even though it's really fast). It can lead to a lot of boilerplate.

MobX follows a reactive programming approach. Changes mutate your state, but a bunch of behind-the-scenes machinery keeps this safe and ensures every component knows about every change. This often results in performance gains and leads to less code that you have to write.

Redux is backed by Facebook and used by many industry giants. The community is huge and the mindshare immense.

MobX is backed by a consulting shop from Europe and used by some industry giants. The community is passionate and amazing, but smaller than Redux.

If you're used to Backbone and you've been using it in an idiomatic way, then MobX is going to feel more natural. It follows the same principle of subscribing to data changes as Backbone Models/Views do, but makes it feasible with a smarter engine.

Fundamentally both Redux and MobX give you the same end result: Understandable app architecture with explicit state transitions. A state machine.

What about immutable.js

Immutable.js is great, but I haven't used it personally because I can never tell how much benefit it brings. It's probably a lot like static typing, the bigger your team becomes, the more benefit you get from tools that force good habits.

Redux strongly encourages you to treat your data as immutable, but it's easy to stray. Especially when it comes to large nested objects.

Immutable solves that by implementing immutable data structures on top of JavaScript. If you want to mutate something, you can't.

In theory it has amazing performance but at the end of the day, until immutability is built into JavaScript on the language/engine level, it's not going to be as fast as it could.

reducers, actions, selectors

Let's look at our state machine again.

See the circles? Those represent our state as a result of different actions. We calculate those using reducers.

Reducers are functions that take current state and information about what to do, and calculate new state. Think of them as those functions you pass into .reduce.

const sum = [1,2,3,4,5].reduce((mem, n) => mem+n, 0) // 15

/*

mem n

1: 0 1

2: 1 2

3: 3 3

4: 6 4

5: 10 5

6: 15

*/

Reducer

The Redux reducer performs this same operation on our whole Redux store. We usually write it as a combination of reducers that each take care of their own part of the state tree.

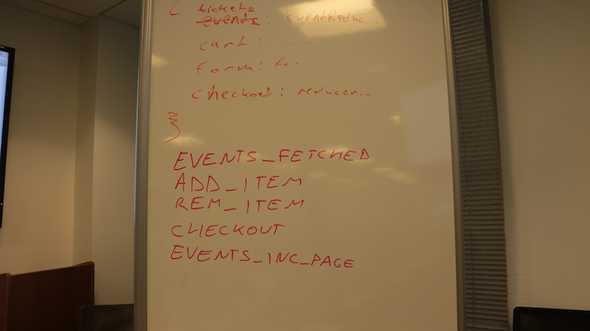

Our app is going to have 4 reducers:

- List of available events

- Shopping cart

- Purchase history and user info

- Transient form state

Redux reducers take the current state, our store, and an action as their input. The action tells them what to do.

Action

Actions are the arrows in our state machine. They tell which state we're transitioning to based on what happened.

Technically actions are objects that have a type and some properties. The type tells reducers what to do, the other stuff gives them data to use.

In practice, actions are functions that return those objects. Action generators if you will.

Selectors

Selectors are functions that help us get data out of our store. Basic selectors don't much more than access values and return them.

More advanced selectors can derive computed values, combine multiple selectors, memoize their results and so on. Using the reselect library for your more complex selectors is a good idea.

Reselect automatically memoizes your selectors to improve performance.

Idiomatic Redux

The community has developed several idioms over the years that make Redux easier to write. They reduce boilerplate, but I fear make Redux code harder to understand for newcomers.

For example, a basic smart component accesses its data store through React context, subscribes to changes, and manually dispatches actions. Like this 👇

class Counter extends React.Component {

componentDidMount() {

const { store } = this.context;

this.unsubscribe = store.subscribe(() =>

this.forceUpdate()

);

}

componentWillUnmount() {

this.unsubscribe();

}

onClick = () => this.context.store.dispatch(incAction()))

render() {

const { store } = this.context;

const state = this.getState();

return (

<div>

{state.count}

<button onClick={this.inc}>+1</button>

</div

)

}

}

Counter.contextTypes = {

store: PropTypes.object

};

We subscribe to store updates in componentDidMount, unsubscribe in componentWillUnmount. When a user clicks the button, we dispatch the incAction.

This gets tedious, so we can use the connect() method instead. That reduces this example to just a few lines:

const Counter = connect(state => ({

count: state.count

}), {

inc: incAction

})(({ count, inc }) => (

<div>

{count}

<button onClick={inc}>+1</button>

</div>

);

Much better isn't it? Sure gets hard to understand if you're not used to it :D

Connect takes 2 arguments:

- A

mapStateToPropsfunction takes data out of state and puts it in component props. This is where you'd use selectors. - A

mapDispatchToPropsfunction takes action functions and wraps them in the appropriate dispatch call

This creates a container higher order component to which you pass your presentational component. It gets data and callbacks from props, renders them, and triggers callbacks when necessary.

If this is too hard to read, you can split it up into separate functions.

const Counter = ({ count, inc }) => (

<div>

{count}

<button onClick={inc}>+1</button>

</div>

);

const mapStateToProps = state => ({

count: state.count

});

const mapDispatchToProps = () => ({

inc: incAction

});

const CounterContainer = connect(mapStateToProps, mapDispatchToProps)(Counter);

Performance

So how slow is it to throw away and rebuild your whole state tree on every change?

First of all, you're not. Depending on how you build your reducers, you can achieve spectacular granulation of changes.

Second of all, here is an example that animates almost 30,000 elements driven purely through Redux. link It even works well on a phone.

If JavaScript can handle rebuilding a 30,000 element array every 16 milliseconds, it can probably handle your state tree too :)

Async actions: Thunks vs Sagas

Things get a little tricky when you want to use asynchronous actions or actions that dispatch other actions.

I like to think of actions as semantic APIs. When you call it from a component, something meaningful has to happen. Otherwise it's hard to fully take business logic out of component logic.

Two approaches exist: Thunks and Sagas.

Thunks

Thunks are enabled by the thunk-middleware. They are actions that return a function. This function gets access to the store and can dispatch more actions.

A common pattern is when fetching data:

function getStubHubEvents() {

return function (dispatch, getState) {

Api.events()

.then(events => dispatch({

type: "GOT_EVENTS",

events

})

.catch(error => dispatch({

type: "ERROR",

error

});

}

}

The main action acts as a semantic API to use in our components, the action dispatched from the fetch Promise tells reducers to do stuff.

This is my favorite approach to build large complex actions. It's clear and does a great job of following the principle of least surprise. Calling an action never results in anything unexpected because you can readily see its whole flow.

Sagas

Sagas are enabled by the saga middleware. They act as observers and react to dispatched actions.

You build sagas as JavaScript generators and use the built-in semantics of putting, forking, calling, etc. to describe what you want and when.

Sagas make it easy to implement channels and other multithreaded approaches to dealing with state updates. They're also a way to achieve canellable actions.

What I personally don't like about sagas is that they're like a weaker more confusing version of MobX. ¯_(ツ)_/¯

Here's what an example Saga looks like:

// worker Saga: will be fired on USER_FETCH_REQUESTED actions

function* fetchUser(action) {

try {

const user = yield call(Api.fetchUser, action.payload.userId);

yield put({type: "USER_FETCH_SUCCEEDED", user: user});

} catch (e) {

yield put({type: "USER_FETCH_FAILED", message: e.message});

}

}

/*

Starts fetchUser on each dispatched `USER_FETCH_REQUESTED` action.

Allows concurrent fetches of user.

*/

function* mySaga() {

yield takeEvery("USER_FETCH_REQUESTED", fetchUser);

}

/*

Alternatively you may use takeLatest.

Does not allow concurrent fetches of user. If "USER_FETCH_REQUESTED" gets

dispatched while a fetch is already pending, that pending fetch is cancelled

and only the latest one will be run.

*/

function* mySaga() {

yield takeLatest("USER_FETCH_REQUESTED", fetchUser);

}

export default mySaga;

The first saga calls a User API and yields a result action when the fetch is done. The other two are different versions of subscribing to the USER_FETCH_REQUESTED action.

We're relying on thunks in our example project. I couldn't find a good excuse to use sagas.